"Why do they live there. Why do they live at all."

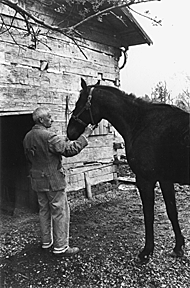

Faulkner at Rowan Oak, 1962. Photograph by Martin C. Dain. Image found here.

Faulkner at Rowan Oak, 1962. Photograph by Martin C. Dain. Image found here.

Back from extended holiday. Here's hoping yours was as restful and bratwurst-filled as mine was.

I've just begun reading Martinican writer and literary theorist Edouard Glissant's strikingly-written book, Faulkner, Mississippi. Part reading of Faulkner from a Creole Caribbean perspective, part personal memoir of Glissant's 1989 experience teaching Faulkner and exploring Faulkner's South, it (so far) reads something like a Faulkner novel as it seems to defer stating its own take on Faulkner even as it speaks of Faulkner's own novels' technique of deferral. Glissant's goal seems not so much to argue something as it is to immerse the reader in his version of Faulkner's version of the South--it's so far very similar, in other words, to Faulkner's approach to his materials in Absalom, Absalom! So, if you liked/didn't like that novel . . .

Early on in Glissant's book, I ran into this passage which puts things in such a way that I don't recall having read anywhere else. You Faulkner fans--see what you think: How can one understand, or at least envision, the South's "damnation"? Is it connected to the South's dark entanglement with slavery, inextricable from its roots and its tormented history?

To these basic, primordial questions the work makes no reply. They remain implicit and unresolved. On the one hand, the work is revealed as infinite, not locked in by any "answer" or solution. On the other, the characters in the work are not "types," determined in advance by possible answers conceived by the author; they are people prey to this gaping wound [of those unanswered questions], to a suspension of being, a stasis, an unhappy deferral acted out through wild exuberance or repressed within. Whether savagely racist, pathologically antiracist, or morbidly indifferent, these people are not compelled by such questions, but they inhabit the vertigo.

The inconceivable and impossible situation of the country (its failure to respond to basic questions) has become an absolute. This is a place of contradiction, where the human situation is not to be studied but should be given a chance to ask the questions. For these reasons, there is no study of character in Faulkner, no so-called narrative weight; rather, we find a vertigo of striking, irremediable people. (22)

UPDATE: In case anyone is curious, I have more to say on Glissant over at Domestic Issue.

3 comments:

What an interesting passage - it does indeed make me want to read this book. I've always been fond of Faulkner - and now, living in about a southern city as one can get - the concept of 'implicit and unresolved' echoes quite true from what I've seen. Perhaps a southerner would say it is impolite to discuss such topics in public.

Interesting.

Pam,

Thanks for the comment. Glissant's approach isn't conventional lit crit but really does seem to arise from his reading of the texts; thus, "theory" per se doesn't also have to be argued with.

You said--

Perhaps a southerner would say it is impolite to discuss such topics in public.

Later on, Glissant notes the troubles Faulkner ran into on just this issue in his public life. Even Faulkner's "go-slow" take on getting rid of Jim Crow laws was too much for many of fellow Mississippians.

Incidentally, something Glissant speaks out of here--and something I'd heard him talk about back in 1992 at LSU--is his trope of the Caribbean and other New World slaveholding regions-as-Plantation: as a vast machine (cultural and ideological as well as a means of production) created by human beings but beyond not just their control but their full comprehension (hence the "vertigo" metaphor in the passage I quoted). Glissant thus reads Absalom, Absalom! as a Carribean novel: Thomas Sutpen's transformation into a Planter--and the event that leads to the destruction of his "design"--occur in Haiti, after all. There are, of course, other ways to read that novel, but Glissant's gets at something that not even the other characters who know Sutpen, and maybe not even Faulkner himself, cannot get at. In that novel, everybody's trying to understand Sutpen's tragic flaw, the best guess being Sutpen's "innocence." I'd say, though, that Glissant's reading would lead us to conclude that Sutpen is genuinely bewildered by the Plantation whose mechanisms he thinks he understands. Glissant talks about almost the whole of Faulkner, but (so far) it seems that Absalom, Absalom! is at the center of his reading.

Thanks for such a thorough response. It all makes me want to read the book even more - especially after having observed life in a 'plantation town' for a number of years! It is bewildering.

Post a Comment